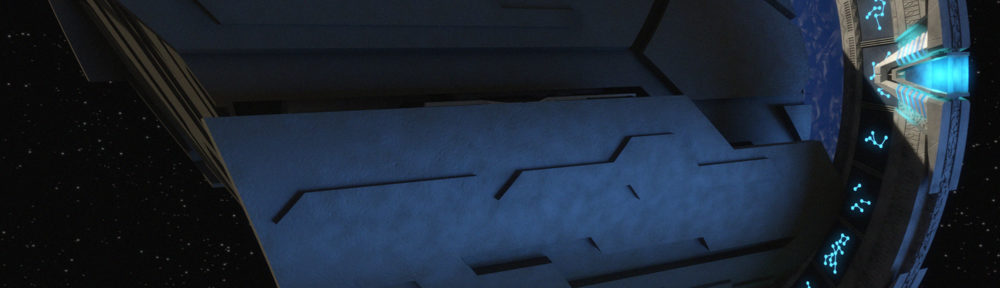

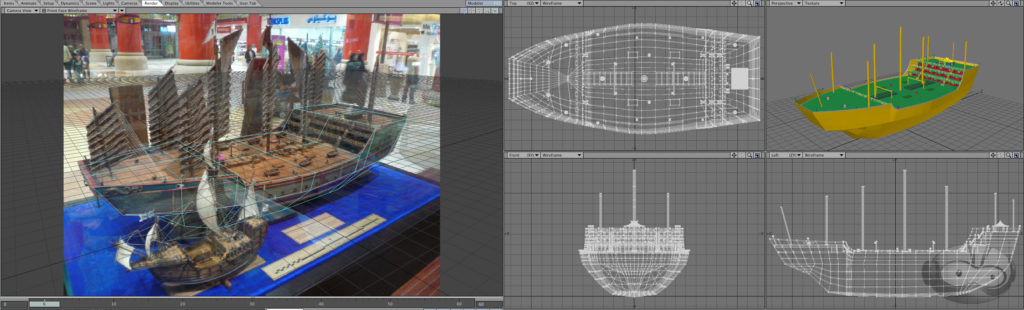

Buildings and vehicles in movies tend to have discrepancies between the exterior and interior, thanks to the realities of filming. It’s difficult to build an exterior mock-up to full scale, or construct an interior set to perfectly match the shape of a model. The Battlestar Galactica from the 2003 remake is a rare exception, and after some examination of it, I was surprised by how much effort went in to matching the hangar deck set with the design of the exterior of the ship. Years ago, I built a rough 3D model of the Galactica hangar, based on the model used for set extensions on the show, and I wanted to complete and expand it at some point. I began looking at the design of the ship in more detail in to start to work out a plan. A couple months ago, I found Lee Stringer’s Flickr, which included a bunch of photos taken of the hangar set, Viper Mark II prop, and the construction blueprints for both that were apparently taken during pre-production of the 2003 miniseries as reference for the VFX team to build their 3D versions. This was the motherlode, and I found that I’d have to restart my model from scratch once I compared it to the actual set drawings.

I don’t quite have the time to knuckle down and actually remake my hangar deck model yet based on this new information, but I can write up all the research and extrapolation I did rather than just keeping it in my brain and hoping I remember it all when I get around to it. I also intend to do posts like this (with increasing amounts of extrapolation) for the hangars of the Blood and Chrome version of Galactica, the Pegasus, the Valkyrie, and the Theseus from “Diaspora,” the fan-made BSG-themed game. I’m going to start with the physical set and CG set extensions, then the exterior model, and then synthesize the two together, including a few areas that logically should exist, but weren’t explicitly seen on the show because they can’t go rebuilding their biggest set every week to make the minority of fans watching with a pause button and a slide-rule happy.

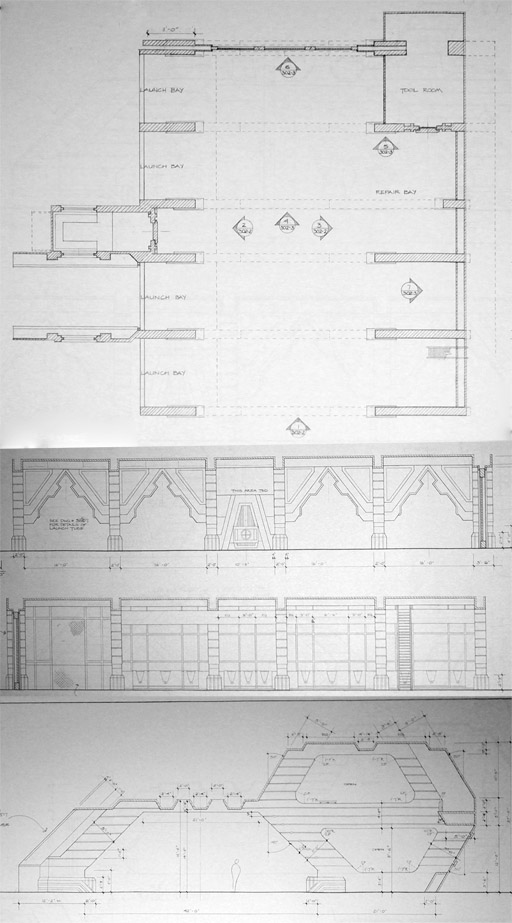

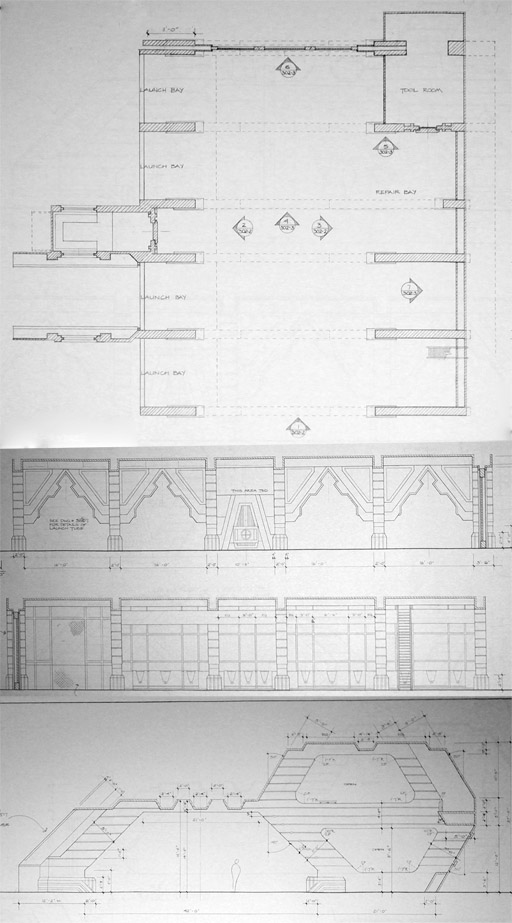

The set of the Galactica hangar deck is a standard segment, consisting of four launch tubes with a control room in between them on the outer side. On the inner side is a series of three semi-enclosed areas (two behind launch tubes and a wider one behind a launch tube and the control room) and a tool room. The tool room has a door leading out to the hangar deck, and another door on the inside, apparently connecting to a corridor.

Each end of the hangar deck can be capped with a variety of endpieces or green-screen set extensions. These are:

Large door

Bulkhead with two personnel hatches

More hangar

Aircraft Elevator

Bare Stage or Plastic Tarps and scaffolding

The Large Door was replaced with a different, more elaborate large door after the miniseries.

Interestingly, the miniseries door continued to appear as a CG element in set extensions for the rest of run of the show, even appearing once alongside the new physical door.

Both versions of the large door appear to be made of three interlocking segments, but they always move as one solid piece when they are shown retracting into the ceiling. There is one exception. In Blood and Chrome, the miniseries-style door was used for the Galactica and the Osiris hangar decks. While Galactica continues the tradition of showing the door as a single solid piece, when Adama’s Raptor launches from the Osiris, you can just barely see the top piece of the hangar door open first, followed by the lower corner pieces retracting to the sides.

The original large door has enough room to retract into Galactica’s bulkheads if it split into three pieces, though the second door would cut through the corridor access in the tool room if it retracted in three seperate segments.

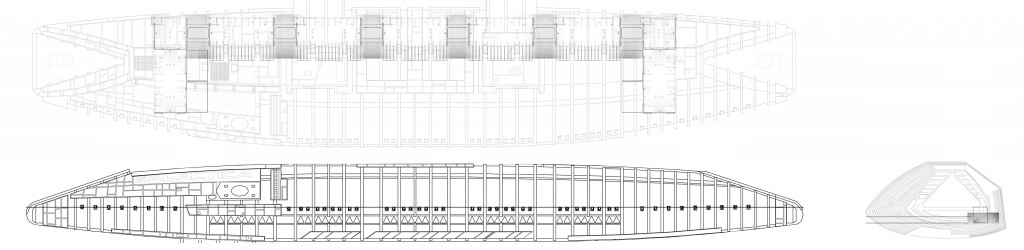

Exterior Model:

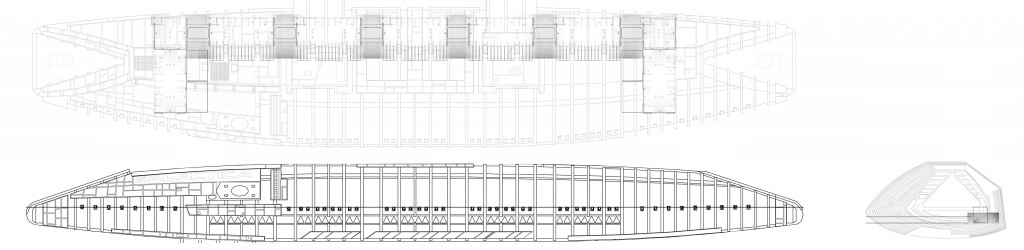

On the Galactica, there are five clusters of eight launch tubes each. Each cluster takes up four “frames” of the hull. The launch tubes in the cluster are arranged with two tubes, then a rib, then four tubes (with a cutout where the rib should be), another rib, and two more tubes. Each cluster is separated by a single empty frame.

The landing deck of the flight pod has a series of regularly-spaced aircraft elevators. These elevators have taxi-lines connecting them to the runway, and have two square… things… in between each elevator.

There is also a dark grey line outlining the elevator. This is a railing that raises from the deck at certain stages of the elevator’s operation, to prevent hapless deckhands from falling in. This was inconsistently depicted during the show.

Synthesis:

The set contains one half of an eight-tube cluster. It’s ambiguous if there are two tool rooms per cluster, but I’m going to go with there just being the one, since it gives more room for Vipers and Raptors, and while having one in each cluster is logical (no sense having to go over hill and dale to get a wrench because a Raptor is being launched and you can’t cut through the elevator), two seems redundant.

Each cluster is bookended by two aircraft elevators, including the outermost ones. That, along with the occasional presence of a bulkhead suggests there is an additional length of hangar, extending beyond the launch tubes and elevators. Budgetary restraints being what they are, the set representing it still had the launch tubes, though they were usually kept in shadow or off-camera during these scenes to downplay it. The shape of the flight pod suggests that they’re half-sized segments, since otherwise they’d be poking out of the hull as it tapers.

The simplest possibly would that the launch-tube side of the additional hangar area just mirrors the inner side, with Viper cubbies and a second-level walkway. Another possibility is suggested by Blood and Chrome, where a couple of shots show a large door identical to the ones that lead to the aircraft elevators on the outboard side of the hangar.

Apparently, they lead to more storage, since a later shot shows a pair of Landrams parked behind them. There are a couple of different way these endcaps might sprawl out behind those doors, such as having elevator-sized garages, or even a few additional identical sections of hangar.

I’m going to go with the most capacious option, since there are a lot of Vipers, Raptors, Landrams, and Forklifts that need to be stowed. And who knows where they put those shuttlecraft that are too long for the elevators and too tall for the hangar deck.

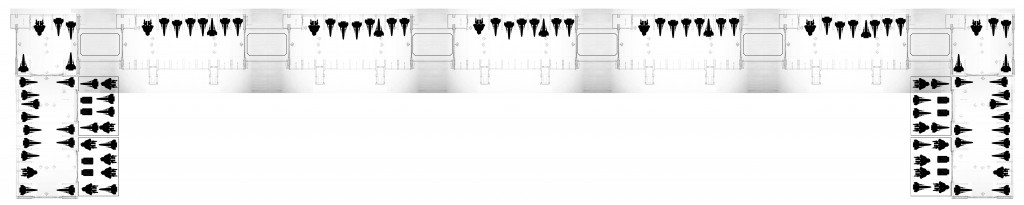

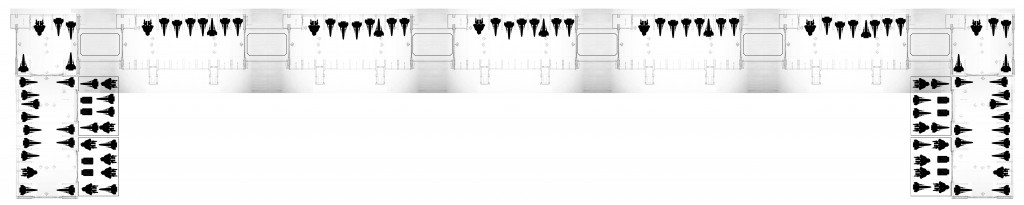

Here’s a layout of the Galactica’s port hangar deck, based on everything we’ve gone over so far.

While I was drafting this, before I finished the illustrations, Lee Stringer added another image to his Flickr (hat-tip to Galactiguise for pointing it out) showing a cutaway of Galactica’s flight pod, explaining more artistically how the hangars, elevators, and launch tubes fit into the exterior model of the ship.

Incidentally, the elevators are numbered 1 through 6, from forward to aft. There are wayfinding signs throughout the hangar (such as HB1/04 or HB9/RB or HB1/34), but I’m going to punt dealing with them until I actually model the hangar, mostly because I can’t figure out how to make them consistent. Either HB# refers to the flight pod, in which case there’s only an HB1 and an HB2, and no HB9, and the second number goes up to 40-something or so, or HB refers the the clusters between the elevators, in which case the second number should never go above 8. And the second possibility leads to the question of whether the port and starboard pods share numbers, so there’s an HB1 in each, or if the starboard pod starts with HB7 and continues to HB12. I’m leaning towards the first option, if only because that’s what the leading zero in the second number but not the first suggests.

Capacity:

In the miniseries, Galactica’s starboard landing deck has been enclosed and converted into a museum. As part of the conversions, the starboard launch tubes were rendered unusable. This apparently was never repaired, and the starboard hangar deck was eventually used exclusively for civilian housing and, probably, Joe’s Bar.

In the second season of the show, the Battlestar Pegasus joined the fleet, and was revealed to have an on-board Viper factory. In season three, Pegasus was destroyed in a suicide mission, after off-loading her Vipers and most of her crew (and probably a ton of other useful supplies and weapons, given that no one ever complained about a shortage of nuclear weapons again). Considering the number of Vipers Pegasus already had on-hand, combined with whatever replacements they built after joining the Fleet, there’s only one reasonable conclusion: For the rest of the run of the show, Galactica had more Mark VII Vipers (and, probably, Raptors) than she could carry, especially with only one working flight-pod.

Behind-the-scenes information says that the Mark VII was harder to fly than the Mark II, since it was designed with computerized features that were removed after the Cylon attack. So, that would explain why Galactica continued operating the Mark II Vipers even when there were enough newer Vipers around to replace them. I’d assume the remaining Vipers and Raptors that didn’t fit on the hangar were either mothballed elsewhere on the ship or in the fleet or were disassembled for parts.

In the Season 4 episode where Galactica donates some Vipers to the Rebel Basestar for their attack on the Cylon Resurrection Hub, Starbuck mentions that half of their planes are with the Baseship, leaving them with 40 “birds,” which may or may not refer to both Vipers and Raptors. There didn’t seem to be much Raptor attrition after New Caprica, and about 16 Raptors jumped out of the starboard landing deck during the assault on the Colony in the finale (the camera move was very abrupt, so it’s hard to be sure, plus there may have been more Raptors that were left with the Rebel Baseship or launched more traditionally from the port pod), so let’s have that as a target, giving us a goal of at least 16 Raptors and between 64 and 80 Vipers in one pod. I began playing with my conjectural hangar layout to see how they might fit in. I tried to find permanent “parking spaces” for each craft, assuming that having them haphazardly floating around the deck isn’t how they’re supposed to be stored long-term, and was just an artifact of Galactica having constant flight operations. And given how often we saw the port hangar deck empty or nearly so (including Starbuck’s Earth-Viper apparently getting it’s own sealed section, because it was too creepy to let anyone fly), leaving some wiggle room so some segments could be filled past capacity while others were emptied makes sense.

This possible layout has 79 Vipers, 21 Raptors, and 8 Landrams, which are close enough to the canonical figures that I’ll say it’s a reasonably accurate extrapolation of Galactica’s maximum air wing, operating one flight pod. Galactica’s present-day sister-ships seen in the Miniseries and Razor, assuming they didn’t preserve the multi-level Blood and Chrome-style hangar deck, would therefore have an air wing of around 200 planes, with about 160 Vipers and 40 Raptors.

Thanks to Lee Stringer, Galactiguise, and the Frak That screencap archive for making this post more possible and/or easier than produce it otherwise would’ve been.